This is a write up for the multiarch1 reverse engineering challenge from Google CTF 2025. Although I registered, I could not play the CTF due to other plans, but I glanced over a few of the reverse engineering challenges and this one looked quite similar to yan85 based challenges I have solved previously on pwn.college, so I wanted to give it a try. Also, this is probably among the easiest since it had more than 60 solves at the time I checked.

Challenge Details

Stacks are fun, registers are easy, but why do one when you can do both? Welcome to the multiarch.

Connection string: multiarch-1.2025.ctfcompetition.com 1337

Files: Dockerfile, crackme.masm, multiarch, nsjail.cfg, runner.py

Starting Point

Analyzing the starting point, runner.py, we can see that a program called multiarch is launched with crackme.masm as an argument.

python runner.py

[I] initializing multiarch emulator

[I] executing program

Welcome to the multiarch of madness! Let's see how well you understand it.

Challenge 1 - What's your favorite number? 131

Seems like you have some learning to do!

[I] done!

./multiarch

[E] usage: ./multiarch [path to .masm file]

./multiarch crackme.masm

[I] initializing multiarch emulator

[I] executing program

Welcome to the multiarch of madness! Let's see how well you understand it.

Challenge 1 - What's your favorite number?

Analyzing crackme.masm

strings crackme.masm

MASM

0 Sg

Welcome to the multiarch of madness! Let's see how well you understand it.

Seems like you have some learning to do!

Congrats! You are the Sorcerer Supreme of the multiarch!

Challenge 1 - What's your favorite number? Challenge 2 - Tell me a joke: Challenge 3 - Almost there! But can you predict the future?

What number am I thinking of?

Everything suggests that crackme.masm is the shellcode that the multiarch runs.

Analyzing multiarch

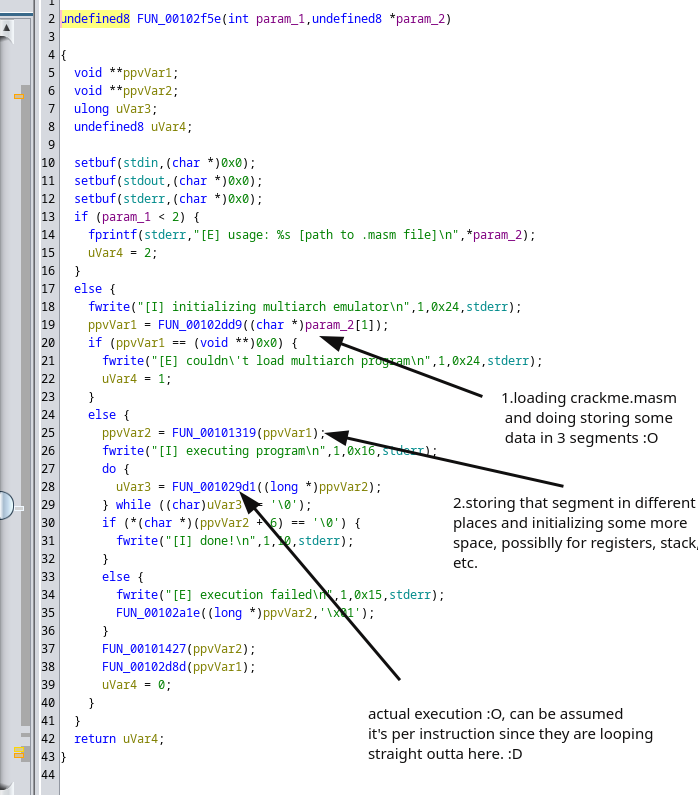

Let us have a look with Ghidra, starting with the main function:

The first two functions seem clear. The second function that is called appears to be for main storage and pointers, but we are not really sure how they are being used at this point.

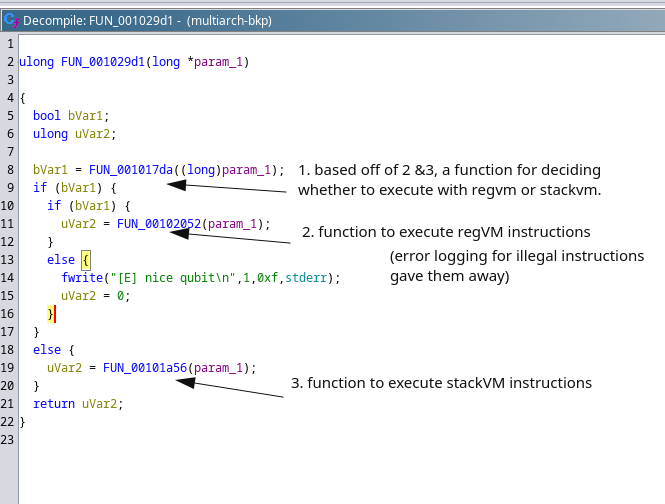

Looking at the third function:

Now we know that there are two VMs and at each instruction it is decided, based on a function, whether it should be executed with regVM or stackVM.

We still have a lot to learn, and since this program is very large, going through it manually would take more than a day. I recently saw a tweet about ghidraMCP and thought I would try it out, it is 2025 after all.

After configuring ghidraMCP with cline (sonent 3.5 free with GitHub edu), I was able to analyze the working of most of the functions and have them renamed inside Ghidra.

crackme.masm structure

After a few more prompts, we had a rough sketch of how the crackme.masm is structured.

[MASM][Seg1Hdr][Seg2Hdr][Seg3Hdr][Seg1Data][Seg2Data][Seg3Data]

^ ^ ^

| | |

4 9 0xE

Where

The segment header contains:

- Type byte (1 for Code, 2 for Data, 3 for Extra)

- Offset (2 bytes) which is where segment data starts

- Size (2 bytes) which is the size of segment data

[0x00-0x03] 4d 41 53 4d // "MASM" Magic bytes

[0x04-0x08] First Header:

01 // Type 1 (Code)

13 00 // Offset 0x13

65 01 // Size 0x165

[0x09-0x0D] Second Header:

02 // Type 2 (Data)

78 01 // Offset 0x178

50 01 // Size 0x150

[0x0E-0x12] Third Header:

03 // Type 3 (Extra)

c8 02 // Offset 0x2c8

2d 00 // Size 0x2d

[0x13...] Code Segment Data (0x165 bytes)

[0x178...] Data Segment Data (0x150 bytes)

Contains strings like "Welcome to the multiarch of madness!"

[0x2c8...] Extra Segment Data (0x2d bytes)

Interesting observations:

1. Headers are tightly packed after magic bytes

2. Data segments start immediately after headers

3. We can see strings starting at 0x178 which matches the Data segment offset

4. Each segment has its specific size which gets mapped into VM memory later

VM state

How VM state is stored through the previously seen second function: (I later had moments where it felt like a few things could be wrong, but I did not check since it did not matter.)

Final VM State Structure (0x88 bytes):

Offset Size Content

0x00 8 Code segment pointer

0x08 8 Data segment pointer

0x10 8 Stack segment pointer

0x18 8 Extra segment pointer

0x20 8 Extra segment size

0x28 8 Flag getter function pointer

0x30 3 Unknown or padding

0x33 4 Program Counter (PC)

0x37 4 Stack Pointer (SP)

0x3B 77 Other VM state (flags, registers, etc.)

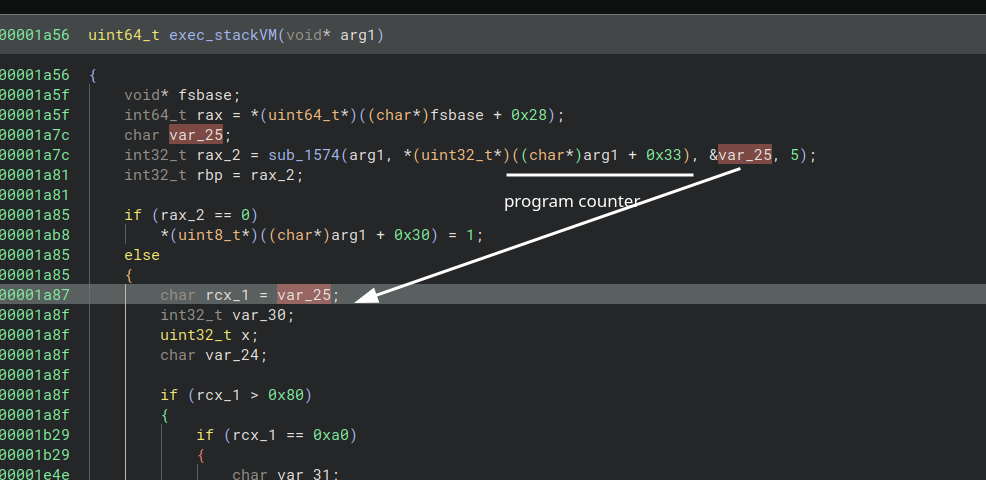

Analyzing VMs

Binary Ninja

While prompting to analyze the VM, I ended up finishing my Copilot tokens limit, but I did receive brief information about what most of the instructions execute, though many instructions were missing.

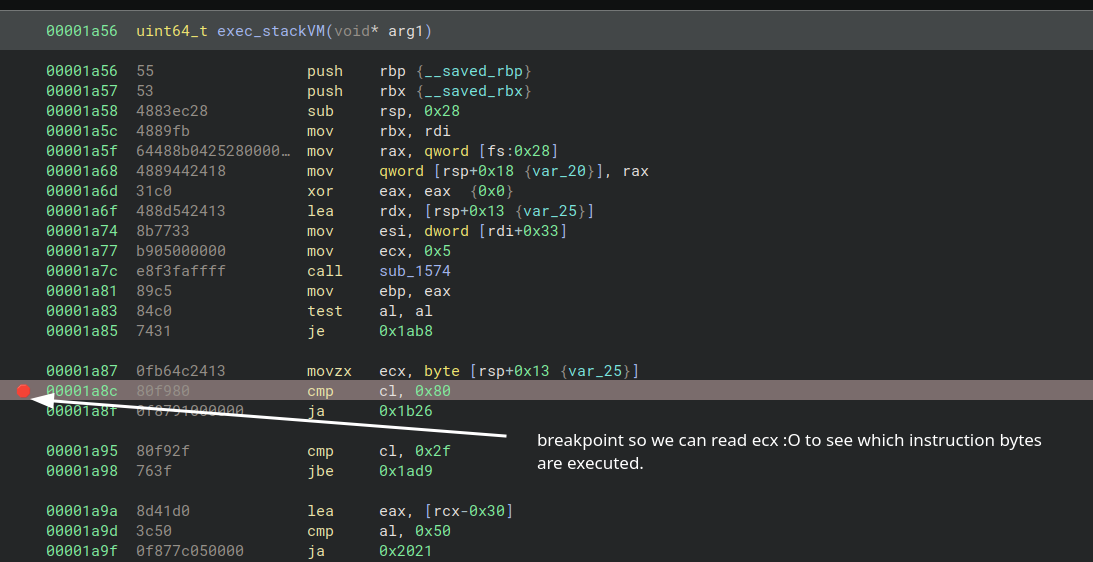

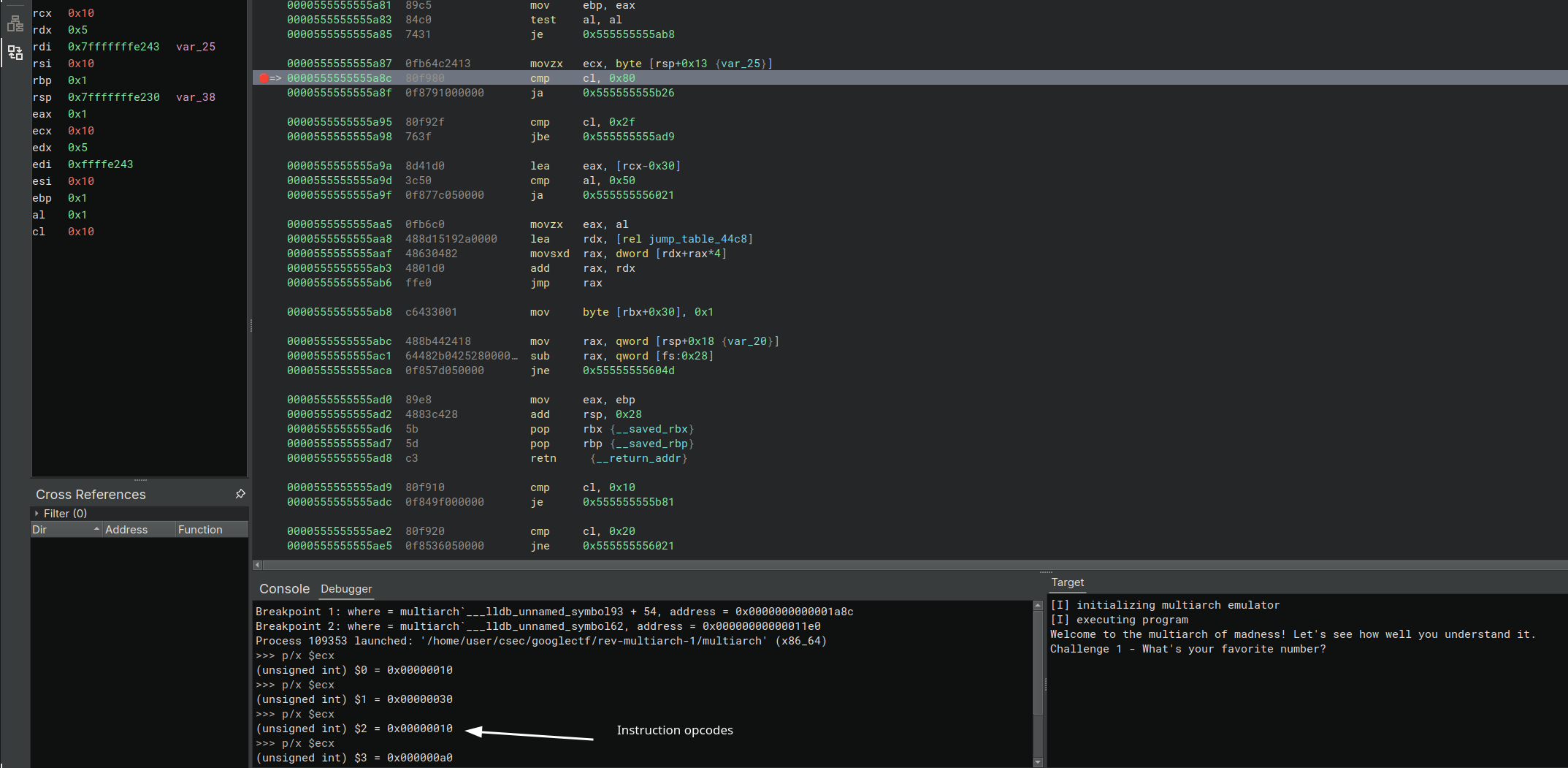

I then used Binary Ninja and started debugging by setting breakpoints at stackVM and regVM:

We need to have an idea about which instructions (opcodes) are executed.

Starting the debugger:

This helps us understand the flow and can be used to gain more information to understand the binary better.

Recreating the VM

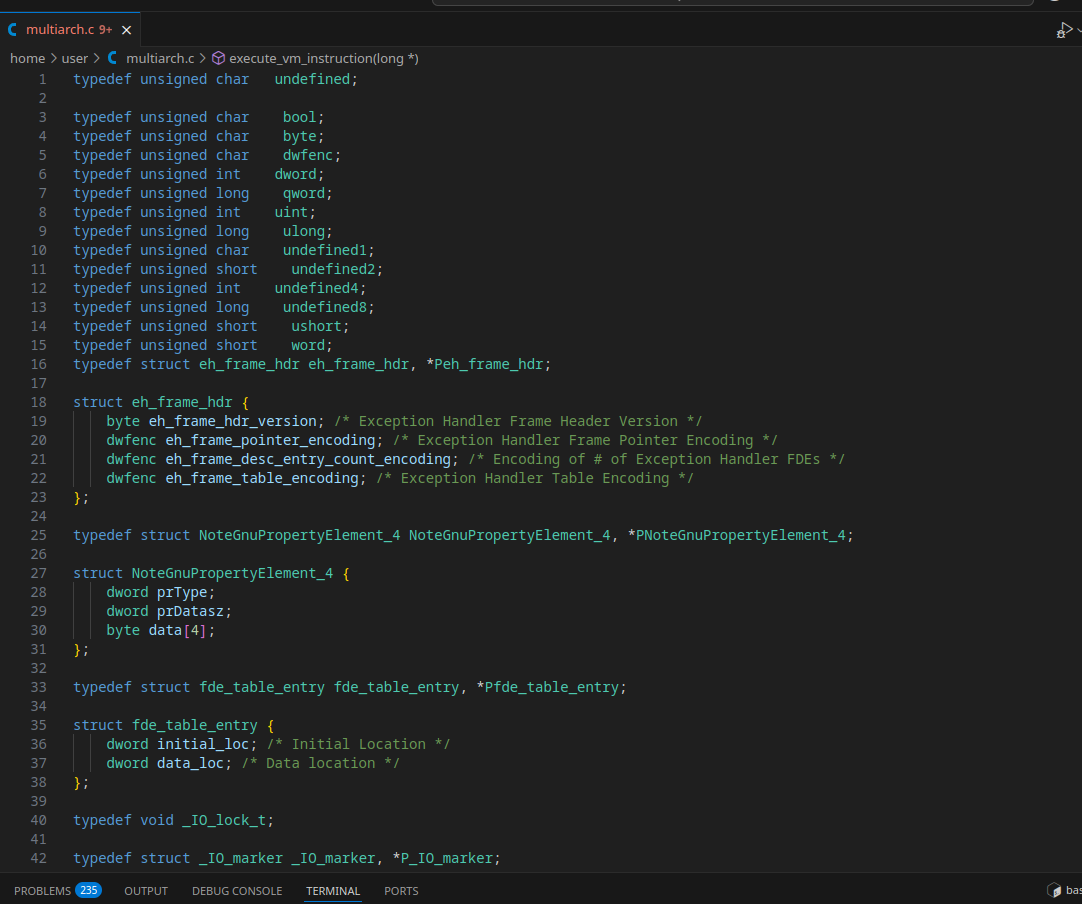

I saved a .c export from Ghidra and started cleaning it up, fixing types (undefined to another, etc.), and then started that program as it would make it very easy to debug and understand what is happening at each stage.

I also had to make certain changes to the code as it did not run as expected, such as not executing system calls on 0x1 (probably due to incorrect changes in types).

Debugging line by line and understanding the working of each instruction, I finally had a working program that was enough to solve the challenge.

Program Source Code | Github Gist

This can be compiled and run with:

gcc -o main main.c ;clear; ./main crackme.masm

Solving the challenges

Challenge 1: What’s your favorite number?

Upon entering an arbitrary number 568 (0x238):

[LOG] execute_stackvm called, pc=0x102d

[DEBUG] Instruction read: a0 00 00 00 00

[LOG] Extended opcode branch, leader=0xa0

[LOG] Syscall validated, local_31=0x2

[LOG] Syscall: read_number

568

[DEBUG] Read number: 0x238

[DEBUG] Wrote 4 bytes to address 0x8efc

[DEBUG] Data written: 38 02 00 00

[DEBUG] Pushed to stack: 0x238

[LOG] pc incremented by 5

...

...

Program Counter (PC): 0x1046

[LOG] execute_stackvm called, pc=0x1046

[DEBUG] Instruction read: 60 00 00 00 00

[LOG] S.ADD instruction

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0x1b505630

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0x238

[DEBUG] Wrote 4 bytes to address 0x8efc

[DEBUG] Data written: 68 58 50 1b

[DEBUG] Pushed to stack: 0x1b505868

...

...

Program Counter (PC): 0x1050

[LOG] execute_stackvm called, pc=0x1050

[DEBUG] Instruction read: 80 00 00 00 00

[LOG] S.CMP instruction

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0xaaaaaaaa

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0x1b505868

[DEBUG] Comparing: 0xaaaaaaaa and 0x1b505868

[DEBUG] Comparison flags set: Zero=0, Negative=1

[LOG] pc incremented by 5

Looking at the logs, we can figure out that the following operation takes place:

x = input + 0x1b505630;

if (x == 0xaaaaaaaa) jump();

Computing such an x:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(){

printf("%u", 0xaaaaaaaa - ((unsigned long)0x1b505630));

return 0;

}

We get 2405061754.

./multiarch crackme.masm

[I] initializing multiarch emulator

[I] executing program

Welcome to the multiarch of madness! Let's see how well you understand it.

Challenge 1 - What's your favorite number? 2405061754

Challenge 2 - Tell me a joke:

So it works.

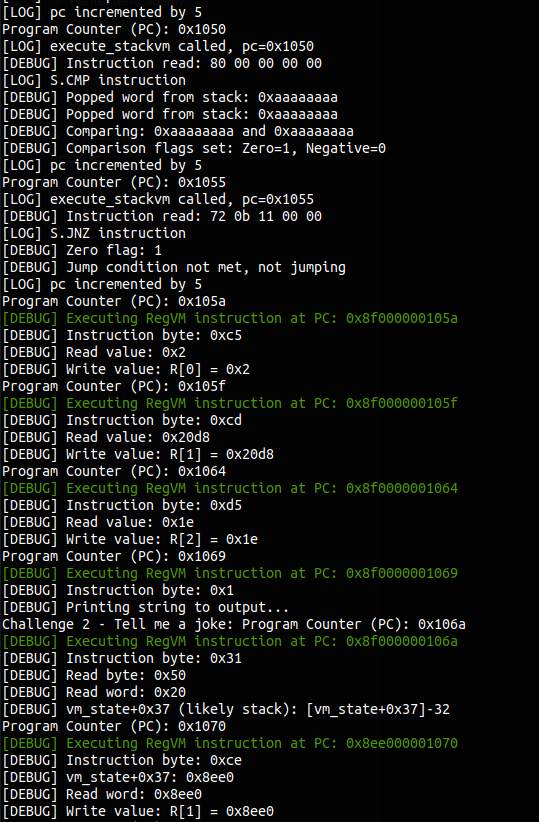

Challenge 2: Tell me a joke

Let us try entering an arbitrary input: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRST:

Program Counter (PC): 0x107c

[0;32m[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8edc0000107c[0m

[DEBUG] Instruction byte: 0x1

[DEBUG] Reading string from input...

[DEBUG] Wrote 32 bytes to address 0x8ee0

[DEBUG] Data written: 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 4a 4b 4c 4d 4e 4f 50 51 52 53 54 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Program Counter (PC): 0x107d

..,

..

[0;32m[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8ed800001125[0m

[DEBUG] Instruction byte: 0xa1

[DEBUG] Read Value: 0xda

[DEBUG] Read word: 0x44434241

[DEBUG] Write value: R[3] = 0x44434241

[0;32m[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8ed800001127[0m

[DEBUG] Instruction byte: 0x51

[DEBUG] Read byte: 0x40

[DEBUG] Read word: 0xcafebabe

[DEBUG] Multiplying: R[3], R[4] = 0x44434241 * 0xcafebabe

[DEBUG] Multiplication result: R[3]=0x8e8c663e, R[4]=0x3620fece

..,

..

[0;32m[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8ed80000112d[0m

[DEBUG] Instruction byte: 0x40

[DEBUG] Read byte: 0x24

[DEBUG] XORing: R[1] = R[1] ^ R[3] = 0 ^ 0x3620fece = 0x3620fece

..,

..

[0;32m[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8ed800001127[0m

[DEBUG] Instruction byte: 0x51

[DEBUG] Read byte: 0x40

[DEBUG] Read word: 0xcafebabe

[DEBUG] Multiplying: R[3], R[4] = 0x48474645 * 0xcafebabe

[DEBUG] Multiplication result: R[3]=0x986a4936, R[4]=0x395028e3

[0;32m[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8ed80000112d[0m

[DEBUG] Instruction byte: 0x40

[DEBUG] Read byte: 0x24

[DEBUG] XORing: R[1] = R[1] ^ R[3] = 0x3620fece ^ 0x395028e3 = 0xf70d62d

..,

..

Multiplication and xor happens several times

...

..

[0;32m[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8ee000001088[0m

[DEBUG] Instruction byte: 0x80

[DEBUG] Comparing: 0x4e7c5efa and 0x7331

[DEBUG] Comparison flags set: Zero=0, Negative=0

Program Counter (PC): 0x108d

From the entire output, we can note the following operation takes place:

xor_result=0;

for (i (0x8ee0); i<=0x8f00; i++){

val = 0xcafebabe * (unsigned int)input[i];

xor_result= (unsigned int)(val >> 32) ^ xor_result;

}

if(xor_result==0x7331) jump();

We can brute force to find such a number:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

int main() {

uint32_t targets[] = {

0x7331,

};

int num_targets = sizeof(targets) / sizeof(targets[0]);

uint32_t multiplier = 0xcafebabe;

for (int i = 0; i < num_targets; i++) {

uint32_t target = targets[i];

uint32_t found_x = 0;

int found = 0;

for (uint32_t x = 0; ; x++) {

uint64_t product = (uint64_t)x * multiplier;

uint32_t high = (uint32_t)(product >> 32);

if (high == target) {

found_x = x;

found = 1;

break;

}

if (x == 0xffffffff) break; // avoid infinite loop

}

if (!found) {

fprintf(stderr, "Could not find x for target 0x%08x\n", target);

return 1;

}

printf("\"\\x%02x\\x%02x\\x%02x\\x%02x\"\n",

found_x & 0xff,

(found_x >> 8) & 0xff,

(found_x >> 16) & 0xff,

(found_x >> 24) & 0xff);

}

return 0;

}

We get the string \x46\x91\x00\x00.

We need to input the code through echo:

echo -ne "2405061754\n\x46\x91\n" | ../multiarch crackme.masm

[I] initializing multiarch emulator

[I] executing program

Welcome to the multiarch of madness! Let's see how well you understand it.

Challenge 1 - What's your favorite number? Challenge 2 - Tell me a joke: Challenge 3 - Almost there! But can you predict the future?

Challenge 3: Almost there! But can you predict the future?

Let us re-enter our arbitrary number 568 (0x238) again.

[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8ee0000010b2

[DEBUG] Seeding random number generator...

[DEBUG] Seed value: 0x238

...

..

[LOG] execute_stackvm called, pc=0x114f

[LOG] Syscall: get_random

[DEBUG] Random number generated: 0x92d736cc

[DEBUG] Pushed random number to stack: 0x92d736cc

...

..

[DEBUG] Executing RegVM instruction at PC: 0x8edc00001155

[DEBUG] XORing: R[0] = R[0] ^ R[1] = 0x133700 ^ 0x92d736cc = 0x92c401cc

...

..

[LOG] execute_stackvm called, pc=0x115d

[LOG] S.XOR instruction

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0xf2f2f2f2

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0x92c401cc

[DEBUG] Pushed to stack: 0x6036f33e

...

..

[LOG] execute_stackvm called, pc=0x10c3

[LOG] S.AND instruction

[DEBUG] Wrote 4 bytes to address 0x8edc

[DEBUG] Data written: 3e f3 36 00

...

..

[LOG] execute_stackvm called, pc=0x10cd

[LOG] S.CMP instruction

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0xc0ffee

[DEBUG] Popped word from stack: 0x36f33e

[DEBUG] Comparing: 0xc0ffee and 0x36f33e

...

..

Random numbers are generated and the next steps are reproduced.

From the above, we can note that the following operations take place:

for(int i(0); i<=some_n;i++){

x= input;

seed_random(x);

y= random();

if(((y^0x133700 ^ 0xf2f2f2f2)&0xffffff)==0xc0ffee) jump;

}

Although the seeding is done with a standard srand() function, the random generation function is defined as below:

uint64_t vm_syscall_get_random(long * param_1,unsigned int *param_2)

{

unsigned int uVar1;

int iVar2;

uVar1 = rand();

*param_2 = uVar1 & 0xffff;

iVar2 = rand();

*param_2 = *param_2 | iVar2 << 0x10;

return 1;

}

Hence, we need to take care of it as well.

So we can brute force it with the following code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

int main() {

uint32_t target = 0xc0ffee;

uint32_t mask = 0xffffff;

uint32_t const1 = 0x133700;

uint32_t const2 = 0xf2f2f2f2;

for (uint32_t n = 0; n < 0xffffffff; n++) {

srand(n);

uint32_t r1 = rand();

uint32_t r2 = rand();

uint32_t r = (r1 & 0xffff) | (r2 << 16);

uint32_t x = const1 ^ r;

uint32_t y = const2 ^ x;

if ((y & mask) == target) {

printf("Found n: %u (0x%x)\n", n, n);

printf("rand() = 0x%x\n", r);

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

Running the above, we get 45483068 (0x2b6043c).

echo -ne "2405061754\n\x46\x91\n45483068" | FLAG=MYFAKEFLAG ../multiarch crackme.masm

[I] initializing multiarch emulator

[I] executing program

Welcome to the multiarch of madness! Let's see how well you understand it.

Challenge 1 - What's your favorite number? Challenge 2 - Tell me a joke: Challenge 3 - Almost there! But can you predict the future?

What number am I thinking of? Congrats! You are the Sorcerer Supreme of the multiarch!

Here, have a flag: MYFAKEFLAG

[I] done!

It works.

Obtaining the flag

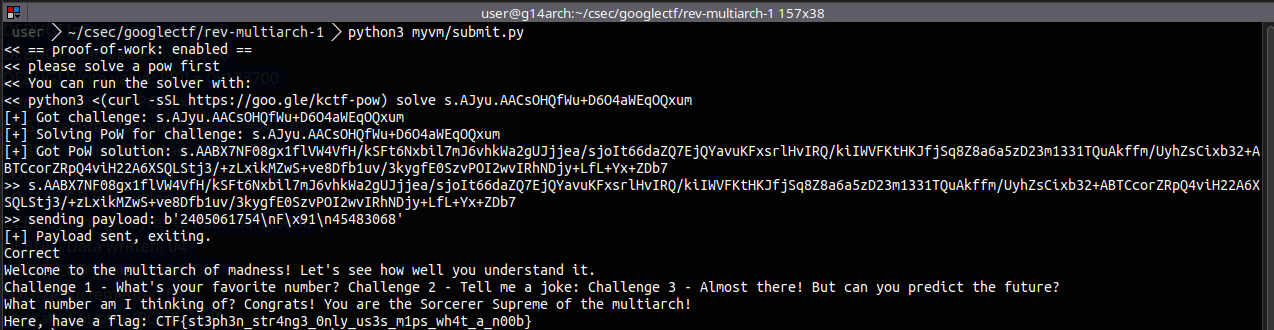

With a script to solve the proof of work and submitting the solution: :D